JAMES BAY

AN ESSAY IN 58 IMAGES

Looking down from space at night, northern Quebec looks vast and empty. The international border disappears, replaced by a striking juxtaposition – the brightness of electric civilization and the quiet dark of the northern forest. Only the few lights of Cree and Inuit communities, and the necklace of dams on the La Grande River, hint at any northern population, or at the connection between these vastly different realities.

If you live in New England as I do, then your life is intimately tied to James Bay, whether you know it or not. And no matter where you live your life is connected to Indigenous people who you might not even have imagined.

There are people in that forest and they have lived there for as long as the forest has been. For nearly five thousand years now this has been Eeyou Istchee, the People’s Land.

So much of that history is ethereal when you look out on the land.

For most of those five thousand years, Cree culture has been as biodegradable as the forest which provided it sustenance and shelter.

If you don’t look carefully, you can miss the continuing legacy of sovereign occupation. Though much has changed, Cree culture remains strong in this forest. This has been the lesson for me over the last forty years.

I went there first to discover a wilderness, to discover a place wholly separate from the world I knew.

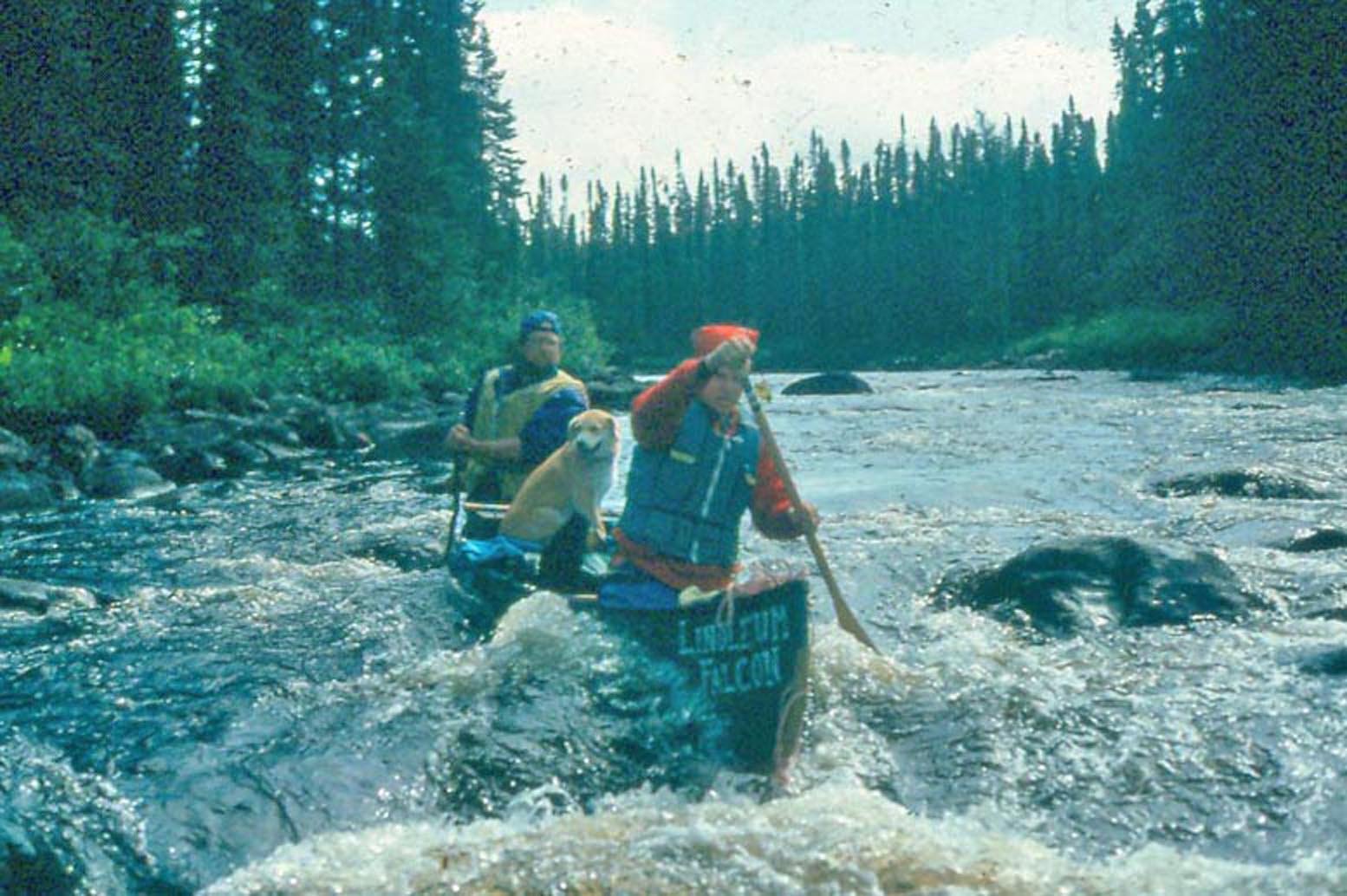

I was looking to adventure in the big woods and to paddle wild rivers.

What I found was a place of immense beauty.

And, I found big rivers.

As well as deep woods.

What I never found was a wilderness,

Only a complicated landscape,

A landscape of deep contradictions where many forces were at play.

I found a place where a 21st century First Nation stands on the frontlines of global resource extraction,

And a place where indigenous people know the history of the resource frontier and of colonization.

I also found a place where culture is strong, a place where people are determined to not forget or be forgotten.

Today, when I go to Eeyou Istchee, I travel mostly by truck,

And camping has become an odd juxtaposition of vocations.

The roads go everywhere now,

Even to places that it used to take a month of paddling to reach.

There are two storylines to follow then, the story of resource extraction and the story of Cree culture in the 21st century. They are tightly tied to one another now, for better or worse.

Eastern James Bay is the size of New York and Pennsylvania, and though it was one of the first places involved in the Canadian fur trade, it remained relatively isolated until the 1970s.

This was when the province of Quebec began to build the James Bay Hydroelectric Complex.

Over the last fifty years, the region has been engineered to produce massive amounts of power for the Canadian and US markets and has become the focus of industrial logging to fill Canadian and US lumber needs.

There are few places now that have not been impacted by one or both industrial uses.

Four major river systems have been combined to focus water on the La Grande hydro dams. This is the Eastmain River, which is 90% diverted. The lighter green alder bushes here are showing you where the river used to flow.

The scale of the control structures is hard to capture in a photo. This is the Giant's Stairway at LG 2 at Radisson. Each stair is the size of three or four football fields.

The high-tension lines dominate the landscape for miles along the many corridors that run south.

Sometimes they look as thick as the black spruce over which they loom.

The substations are audible over many miles, especially when the sun goes down and people in the south turn on lights and start cooking dinner.

This is the upper Rupert before its diversion in 2013. I like to think I caught the river’s spirit dancing that day.

The forests of Eastern James Bay are dominated by black spruce and jack pine, both of which grow smaller going north until the taiga gives way to the true tundra along the Great Whale River.

Trees grow very slowly in the region, so sustainable forestry practices which work quite well in the south are not economically viable.

Clearcuts go on for hundreds of hectares turning the landscape into something that looks like the moors of Scotland.

There are three large mills where most of the timber is taken for process. The trees are small in James Bay, so they get turned into 2x4s and smaller.

These mills work on a scale that makes them profitable, even though the trees are small.

When the market is hot, both the loggers and the mills work 24 hours a day.

The lumber is then taken south by rail. The next time you are in the lumberyard, look for the names Barrete-Chapais and Chante-Chibougamau.

This will only go on for another 10-15 years before all the merchantable timber is cut. No one really knows if it will ever grow back, given the changing climate conditions.

This is the state of things after fifty years of massive extraction, but the forest remains in places.

The rivers still run on in places,

Rolling and boiling as they have done for thousands of years,

Winter and summer.

The land is still beautiful.

The people are still there.

But this is where it gets more complicated,

Because the story of people is one of both change and continuity.

This is the village of Mistissini in 1968, before the hydro development.

This is Mistissini in 2007, less than two generations later.

The changes across this vast region are hard to grasp.

There is Cree government and a Cree Regional Authority which interacts with both the government of Quebec and politicians in Ottawa.

These politics sometimes involve protest.

Young people especially, making their voices heard about the land which they still claim.

They speak to Ottawa, too.

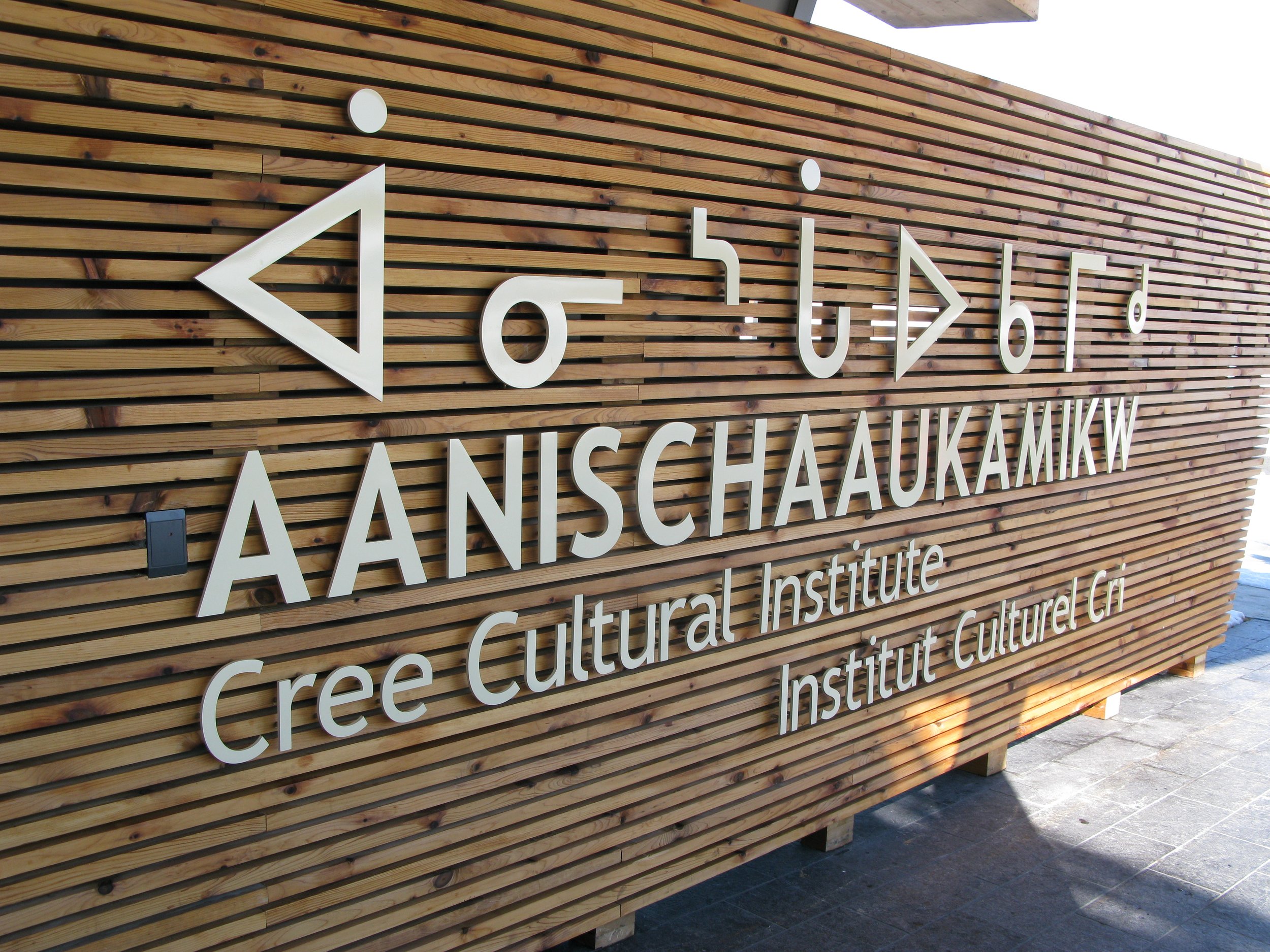

Culture is now protected in a world-class museum and research facility.

Aanischaaukamikw, the “house of carrying knowledge forward.”

And culture is still on the land.

It is still being passed down in the everyday life of the communities.

And out on the land.

Winter and summer.